Layne Fargo’s novel The Favorites is set in the world of competitive ice dancing; as you would expect, much of plot of the novel is anchored to high-suspense competition scenes. What you might not expect is that these scenes all have a much higher percentage of interiority than action when you look closely at them.

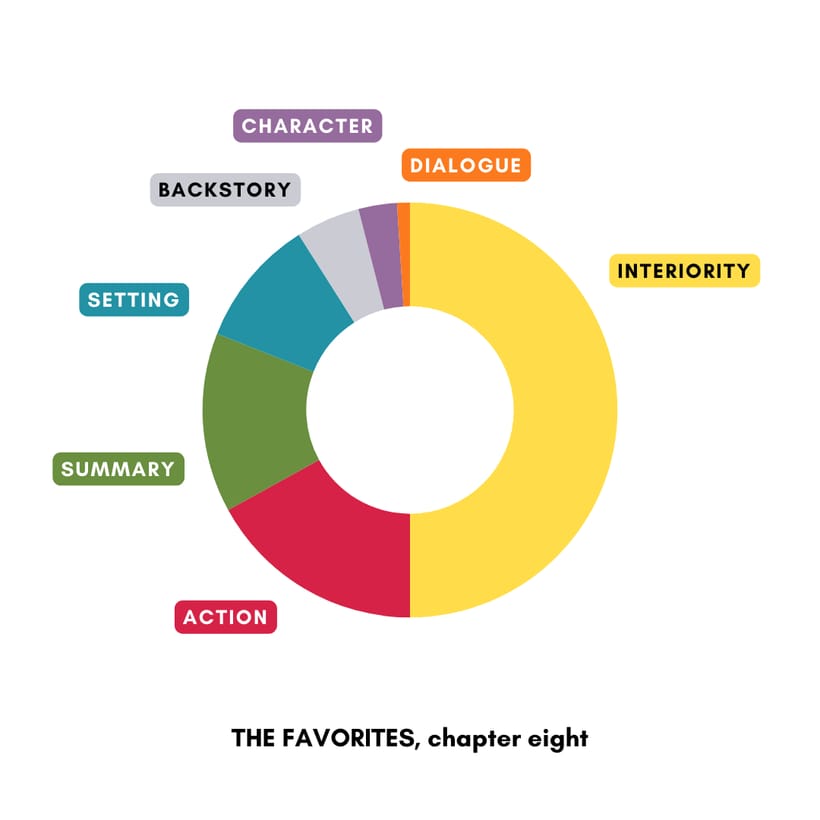

Let’s walk through chapter 8 of the novel, the first competition scene, and see how Fargo is using her palette of scene components. To start, here is the percentage breakdown:

Interiority: 50%

Action: 17%

Summary: 14%

Setting: 10%

Backstory: 5%

Character: 3%

Dialogue: 1%

As always, these are rough numbers—someone else doing the tagging might come up with different numbers or even categories—and there is no one perfect formula for a perfect scene. We can’t write scenes by numbers.

Now let’s take a closer look at how the scene works. We open in summary on the last day of the competition. It’s the late 1990s at the National Ice Dancing Championship in Cleveland, Ohio. Kat Shaw and Heath Rocha are teenagers competing in their first major competition. The stakes are high: Winning a medal is their only hope for attracting the sponsorships and coaching they need to keep competing. And the odds are stacked against them: Kat has lost both of her parents, Heath is in foster care, and they’ve had to scrape together funds for what training and equipment they do have.

Fargo increased those odds, and thus the suspense, in chapter 6, when Bella Lin runs into Kat during a practice session, sending her slamming into the ice and injuring her hip. Bella and her twin brother Garret are Kat and Heath’s main competition and opposite from them in almost every way: They are the children of Sheila Lin, herself an Olympic gold ice-dancing champion and now their coach.

The summary sentences (A, in the graphic above) focus on Kat’s injury, reminding us of the high odds: “I broke it down into small, manageable steps, like in training…. I got through the day one excruciating moment at a time.” And then we get a tiny bit of setting (B) as Heath and Kat wait to skate.

At this point we get our first action of the scene (C): “He stood behind me, palm pressed against my stomach, and we took slow, deep breaths together until we felt our pulses beat in sync.” Fargo then uses two sentences of interiority (D) to draw out this hushed, tense moment before they begin. We learn that Kat always feels calm when she and Heath are touching, and we’re reminded that this could be their last competition. Fargo is deepening our knowledge of the relationship between the two, drawing us closer to our protagonist and narrator, Kat, and reminding us of the stakes, just as she used the opening sentences of the chapter to remind us of the odds.

Only now does the performance begin, as they skate out to center ice (E). Half a page later, the performance ends with a final action, “a quick, chaste kiss” (F). In between there are only two other action beats: “we wound ourselves around each other in a sinuous combination spin” and “We ended with a standing spin that left us facing each other, Heath’s hands around my waist.”

Fargo doesn’t break the performance down moment by moment or include a lot of detail about their movements. The real drama of the scene, it turns out, is located at the end as Kat and Heath wait for their scores—a bit of drama Fargo chooses to end on a cliff-hanger rather than resolving. For the first half of the scene, during the performance, Fargo instead uses a combination of setting, summary, backstory, and interiority to help us sink into what it feels like to be Kat during those four minutes.

Look at this passage, for example, which comes immediately after they skate out to begin the performance:

I let it all fall away. Not just the pain—everything. The hum of the crowd. The scrape of our blades. The sound of the announcer saying our names. Everything faded, until my focus shrank to the heat of Heath’s fingers intertwined with mine.

Those setting snippets (the crowd hum, skates scraping, announcer) are all sound, perceptible to anyone in the arena, but they are surrounded by sensory feelings (the pain, the heat of Heath’s fingers) only perceptible to Kat—and only accessible to the reader via her interiority.

After this passage, we get a bit of summary, telling us they were skating to a medley of songs from Madonna’s Ray of Light album, a detail immediately deepened by a snippet of backstory, which reminds us of what Kat’s trying to escape—her poverty and the custody of her drug-addicted and violent brother: “Heath had recorded it off B96 for me, and I’d worn out the cassette, playing it over and over until Lee smacked the wall and shouted to turn that shit off.”

The rest of the performance section of the scene toggles back and forth between action—those spins—and interiority, most of which is again focused on what Kat is feeling: Heath’s breath on her neck, the burning in her legs.

But there are two other bits of interiority I want to call attention to here because they give us a glimpse into a narrative choice that contributes to the success of the novel. Before the summary material, we get this sentence: “I don’t remember much about that free dance.” And immediately after the backstory snippet: “Here’s what I do remember about our first national final…”

These two snippets remind us that our narrator isn’t the Kat who is sixteen during this performance. The present tense verb “remember” signals that we are hearing directly from a middle-aged Kat, one who is telling her story her own way, countering the documentary being released on what she describes in the first page of the novel as “the worst day of my life.” Later we learn that this worst day is the final day of competition of the 2014 Sochi Olympics, a full fifteen years after this scene of Kat and Heath’s first competition. This retelling then is inevitably shaped by everything that comes after, and Fargo is here adding another layer of mystery to a novel that is already full of drama: Is Kat a reliable narrator of her own past?

Enjoyed this piece? Make sure you are signed up for the Novel Study newsletter, which goes out whenever I have a new essay ready for you.

Want more craft analysis like this?

Novel Study examines techniques from novelists like Ann Patchett and N.K. Jemisin, translating them into practical tools—complete with full-color charts illustrating how successful stories are built.