Layne Fargo’s novel The Favorites is about a (fictional) ice dancing competition at the (real) 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. There is high drama at the competition and plenty of additional drama in the decade leading up to the event. Fargo could have chosen a straightforward narration style for this novel and relied on her twisty plot, the built-in drama of competitions, and the intense central romance to draw readers in. Instead, she chooses a narrative style with a lot of layers, which adds an element of mystery to the novel. Readers become sleuths in pursuit of the ‘real’ story.

Her narrative frame is likely inspired by Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, which Fargo cites as one source text for the novel. Many people forget about the frame narration of Wuthering Heights—in part because the Heathcliff and Cathy drama is so compelling and in part because Brontë doesn’t weave in and out of the frame narrative frequently. Let’s walk through how Brontë uses the technique before we see how it works in The Favorites.

Here are the first lines of Wuthering Heights (which you can read for free via Gutenberg.org):

1801—I have just returned from a visit to my landlord—the solitary neighbour that I shall be troubled with. This is certainly a beautiful country! In all England, I do not believe that I could have fixed on a situation so completely removed from the stir of society. A perfect misanthropist’s Heaven—and Mr. Heathcliff and I are such a suitable pair to divide the desolation between us. A capital fellow!

The “I” here, we learn, is a Mr. Lockwood, and he soon shows himself to be spectacularly obtuse—as blind to his own nature as he is to the social cues of the people he meets. Brontë’s brilliance shows in this bit of fun savagery: She lets Lockwood unwittingly expose his own flaws through his first-person narration. Despite describing himself as a solitary misanthrope and receiving a chilly welcome from Heathcliff, Lockwood decides to visit again the very next day and must spend the night due to a snow storm. During the night, he discovers Cathy’s childhood diary, and we get a few snippets from that, before he dreams of her ghost outside his window in the storm.

We soon encounter our next narrator, the housekeeper Nelly Dean, who relates the whole saga of Heathcliff and Cathy to Lockwood while he is recuperating from an illness brought on by his ill-advised visit. Nelly takes over the first-person narration, with infrequent references to Mr. Lockwood as “you.”

A lot has been written about this narrative frame, but for our purposes I want to focus on how it affects the reader. Here’s how we can visualize it:

The Heathcliff and Cathy saga is the central story. Nelly Dean is a direct witness to the events of the story. She tells them to Lockwood, who writes down the story, along with his frame narrative, for an unspecified audience. As readers then, we experience the story through these various narrative layers: Nelly’s interpretation of what she sees and chooses to tell Lockwood, then Lockwood’s possible shaping of what she tells him. We never get direct access to the interior thoughts of Heathcliff or Cathy.

In comparison, Fargo opens the book in the first-person, present-tense point of view of Katarina, who is the Cathy parallel in her story:

Today is the tenth anniversary of the worst day of my life. . . . Maybe you're planning to snuggle up on your sofa tonight with a bowl of popcorn and binge the documentary series released to commemorate the occasion. Schadenfreude and chill. Go right ahead. Enjoy the show.

That “worst day,” we soon learn, is the 2014 Olympic ice dancing performance of Kat and her boyfriend and partner Heath. Fargo is creating an implied 2024 reader/viewer here—the “you” Kat addresses already knows the basics of what happened that day. And the relationship between our narrator Kat and that 2024 implied reader is antagonistic. The 2025 reader is drawn in by the secret: What do those fictional 2024 readers know that we don’t? What did go down at that Olympics? And we are also a tiny bit suspicious of our narrator: How truthfully will she tell her own story?

The next lines only increase that tension. Kat warns, “Don't fool yourself into thinking you know me” and reels off a lists of names she’s been called: “a bitch, a diva, a sore loser, a manipulative liar. Cold-blooded, a cheater, a criminal. An attention whore, an actual whore. Even a murderess.” But, she declares, “I don't give a damn anymore. My story is mine, and I'll tell it the same way I skated: in my own way, on my own terms. We'll see who wins in the end.”

Kat’s declaration is immediately undercut when we turn the page to find ourselves in the opening scene of the documentary. A narrator solemnly intones, “They were an obsession… Then a scandal” over visuals of Kat and Heath. We also hear the voices of four interviewees. The first two are wonderful nods to Brontë’s frame narrative: sports commentator Kirk Lockwood and former ice dancer Ellis Dean. 2025 readers get a few clues about what happened, the most dramatic of which is a shot of “bright red spatters” staining the Olympic rings on the ice rink in Sochi.

Both of these pieces are positioned as a prologue. When we move to chapter one, we find ourselves in the first person, past tense: “Once I was satisfied, I handed him the knife. Heath stood up on his knees, and I stretched out on the warm spot he’d left on the bed, watching him.” We discover that this is sixteen-year-old Kat, c. 1999, but our 2024 Kat is still present in flashes. For example, we learn that they are about to travel to Cleveland for their first National Championship: “I was certain the competition would change everything for us. I was right. Just not in the way I imagined.”

After chapter one, we find ourselves in the documentary once more, which gives us some background about Kat’s start in skating and how hard it is for female ice dancers to find male partners. That pattern continues as the novel unfolds, with the documentary segments appearing every few chapters. More and more commentators are gradually introduced into these segments and, not too far into the book, we also see these same commentators pop up in Kat’s narrative as characters.

At the beginning of the novel, Kat is positioned as an unlikeable and possibly unreliable narrator, while the talking heads in the documentary seem to be sharing the truths that we haven’t witnessed for ourselves. By the end of the book, we know that some of these interviewees have their own agendas, their own roles to play in the plot, and their commentary may be just as self-interested as Kat’s.

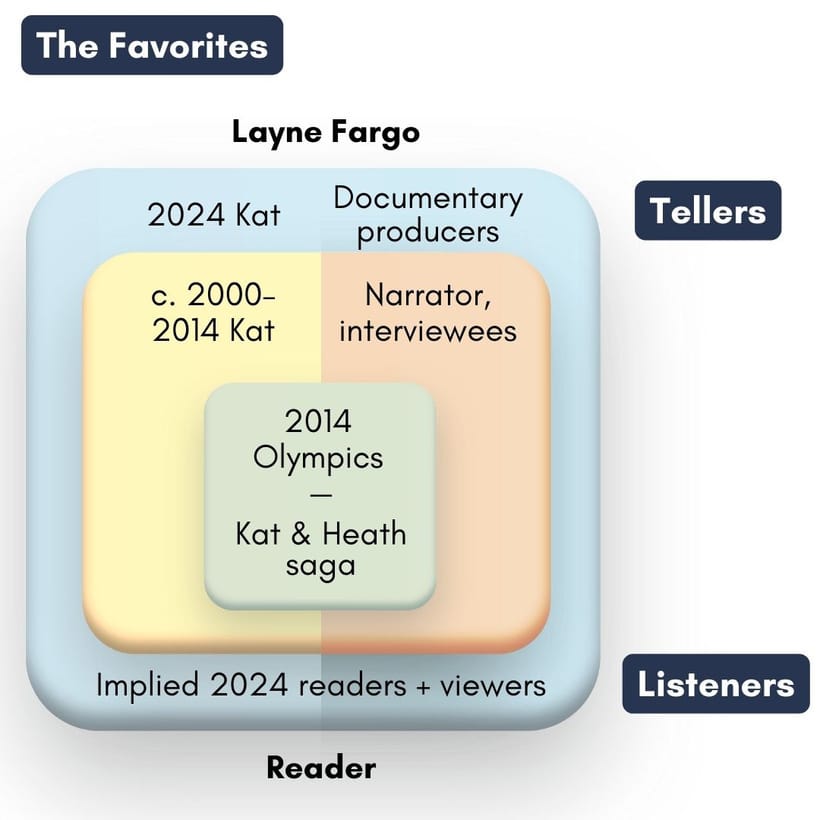

Here’s a visual of the way the narrative layers work in The Favorites:

Rather than nesting her narrative layers, as Brontë does, Fargo makes hers competitive. She also adds energy to the story by dramatizing the implied reader (those 2024 anniversary documentary viewers) and forcing novel readers to decide: Which version of Kat’s story do we think is ‘real’? And do we think she's won in the end, as she declares in the prologue she will?

If you are interested in learning more about the concepts of the implied reader and narrative layers, take a look at Matthew Salesses’s discussion in the excellent Craft in the Real World. This blog post by AC Macklin is also a good summary of a few of the key principles of narratology. Or you can go straight to the sources: Wayne Booth’s Rhetoric of Fiction and Gérard Genette’s “Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method.”

Enjoyed this piece? Make sure you are signed up for the Novel Study newsletter, which goes out whenever I have a new essay ready for you.

Want more craft analysis like this?

Novel Study examines techniques from novelists like Ann Patchett and N.K. Jemisin, translating them into practical tools—complete with full-color charts illustrating how successful stories are built.