SPOILER WARNING

This post discusses the entire plot of Death of the Author, including the ending.

From the moment I started reading Death of the Author, I knew I wanted to spend time thinking through how Nnedi Okorafor uses the three different story strands of the novel to orchestrate the pacing, tension, and emphasis.

From the beginning, Zelu’s plot strand is presented as the primary one. The interview chapters consist of various family members being interviewed about Zelu, and we believe the Robots strand is the Rusted Robots novel we see her begin writing at the end of chapter two. Thus, both of these strands feel like they are extraneous or ‘bonus’ strands—different kinds of primary material that readers might like to see in order to make their own interpretations of Zelu. The page counts support that: Zelu’s chapters occupy roughly 70 percent of the novel, while the Robots strand gets 20 percent, and the interview chapters make up the remaining 10 percent.

Here is a visualization of the three strands of the novel, charting the external intensity of the plots.

You can see right away that the Zelu strand is more intense than the Robots strand: Of the 14 chapters with the highest external intensity, Zelu narrates 9 while Ankara, our Rusted Robots protagonist, narrates 5. Especially in the first half, the interview chapters provide frequent reminders that something significant is going to befall Zelu.

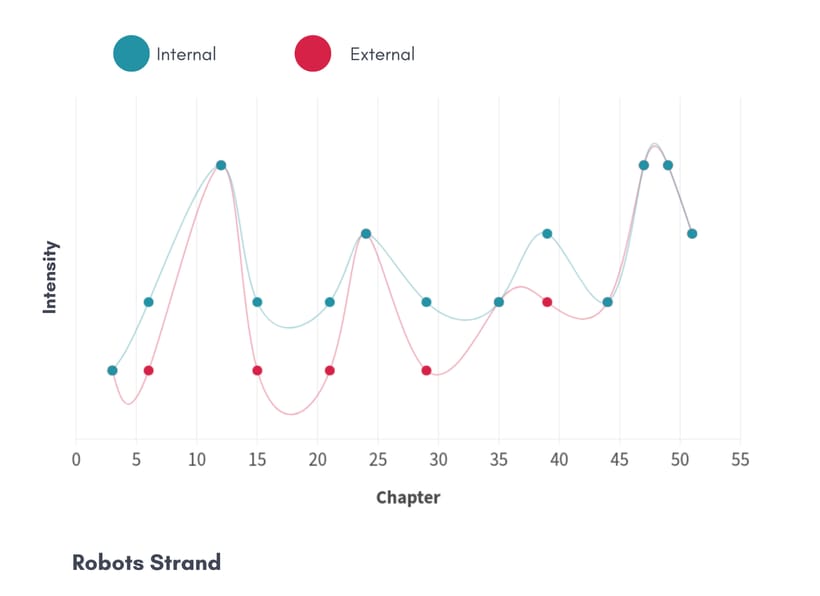

Let’s look more closely at the Robots strand to see how it works before coming back to Zelu. This visualization graphs the internal and external intensity of the plot across the novel.

As I noted in my post on worldbuilding in the novel, the first two chapters are occupied with laying the groundwork for the plot and setting. We learn that Ankara has “terrible news” in chapter 3, and in chapter 6 we learn more about this news and how she got it. We also see her set out on a familiar quest narrative: Her role is to deliver the terrible news—that the Earth is threatened—to her fellow Hume robots, who may be able to avert the threat.

However, in chapter 12, Ankara is beset by a different plot. The Ghosts, a different tribe of AIs, have sent out a Purge intended to wipe out Humes, who they consider to be too like their human creators. Ankara is severely damaged but saved by Ngozi the last human alive on Earth. To help repair Ankara, Ngozi captures and embeds a Ghost, Ijele, in her code. The strategy works, but Ijele has been captured against her will and now cannot get out; Ankara, meanwhile, considers herself infected by this rival AI. Ngozi eventually manages to find a way to allow Ijele to leave, but by this time the two AIs have forged a complex friendship and pledge loyalty to one another after Ngozi’s death in chapter 24.

Ankara resumes her journey and delivers her news to a protected enclave of her fellow Humes who have survived the Purge. Rather than heed the terrible news, however, they are intent on fighting back against the Ghosts, a conflict that force both Ankara and Ijele to make a series of best bad choices between loyalty to one another and loyalty to their tribes. In the climax, Ankara has just delivered a decisive blow against the Ghosts, also putting Ijele at risk, only to discover that the faraway threat is now upon them (chapters 47 and 49).

The Robots strand follows a familiar narrative shape, with recognizable stops and story tropes along the way: the journey, the reluctant hero, the mentor, the unexpected ally, the test of loyalty, the dark night of the soul, and the turning point. Particularly when you look only at the external intensity arc, we can see that familiar shape of rising action to the climax, followed by falling action as the plot resolves.

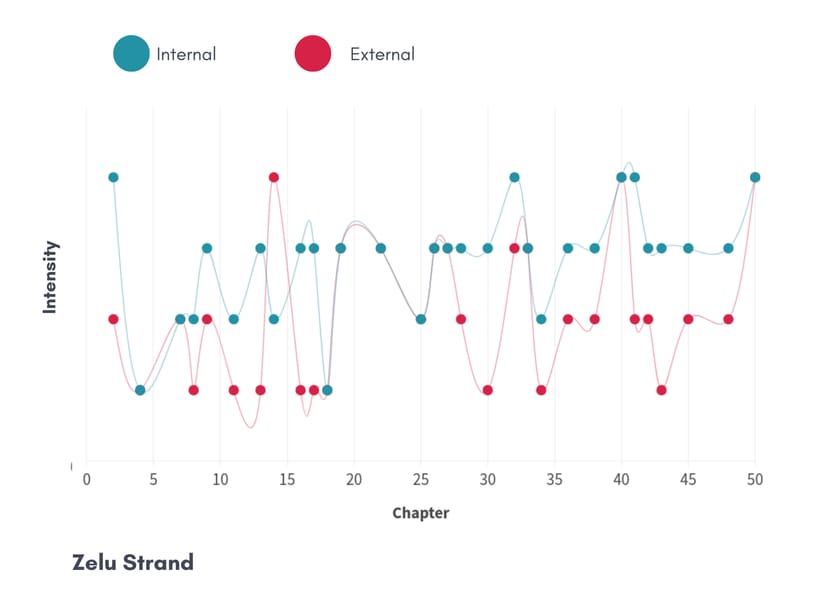

Turning to Zelu’s strand, we see something else entirely. Here’s a visualization of the internal and external intensity of this plot strand:

Notice that the internal strand is consistently at a quite high intensity: Even when Zelu isn’t experiencing something intense, she’s often feeling something intense. She struggles with panic attacks and negative self-talk, which she often hides from others when she can. Of her 30 chapters, 22 of them have an internal intensity of 4 or 5 out of 5. Quite often, the chapters with a gap between a low intensity external event and a high intensity internal feeling are when Zelu is interacting with her family. For example, after she receives the ‘exos’ that allow her walk again, she spontaneously decides to travel home wearing them rather than use her wheelchair. She breezes through the airport, nonchalantly ignoring the stares and comments. It’s only when she is about to walk into her parents’ home that she feels like she is “walking to her death.”

As I noted in my post on the opening, the title and the first interview chapter together work to put readers on high alert when reading Zelu’s point-of-view chapters. Is she going to die? What is the remarkable thing she did or experienced that those interviewed keep alluding to? In chapter after chapter, we wonder Is this it? Is she going to drown herself in Lake Michigan? Is she going to be washed out to sea while swimming with dolphins? Will she be killed by Nigerian kidnappers? And, finally, will she die while going into space?

Each time, she lives but often comes out the other side of the experience transformed. Zelu’s arc is one of continuous evolution: She creates a bestselling novel that propels her to fame, adapts to a cyborg-like existence with her exos, survives a brutal social media dragging, escapes kidnapping in Nigeria, masters firearms as a surprising new extension of her independence, and ultimately ventures into space while pregnant, after receiving an injection that fundamentally alters her DNA to protect against cosmic radiation—taking “another step away from humanity” even as she creates new life within her. Rather than the familiar wave-shaped plot arc followed by the Robots plot, Zelu’s plot is more like a spiral. (If you are interested in reading more about nontraditional plot shapes, check out Jane Alison’s fascinating book Meander, Spiral, Explode—read my review.)

Looking at this list of dramatic events, it’s no wonder that Zelu’s family members portray her in their interviews as a major plot event waiting to happen. The childhood accident that left Zelu a paraplegic also traumatized her family, making them helpless bystanders to Zelu’s calamity even as they struggle to understand her choices.

But there is someone else scrutinizing Zelu, the journalist who interviews her in chapter 9, as part of the advance publicity for her novel. Zelu is immediately on high alert when this “little white guy” pronounces her name correctly and also greets her in Igbo. When he reveals that he’s spoken to the university administrator who fired her, Zelu, on the verge of a panic attack, ends the interview. The episode shows Zelu the dangers of this new evolution; she is on the cusp of fame and fortune, but she now has so much farther to fall. She wrote her novel from “rock bottom,” letting “her mind soar, take her higher and higher. Now nothing was there to keep her from falling and falling, down, down, down.”

The next scene of this chapter is an anomaly. After a summary paragraph telling us that Zelu responded by email to a list of “reasonable questions” from the journalist and the resulting article was fine, without a mention of Zelu’s adjunct career, the scene slides into omniscient narration:

But the one thing Seth Daniels knew was when a story was worth following. And the one thing Zelu never failed to be was a story. Eventually, she would become the defining subject of his journalistic career. He’d follow the highs and lows of her meteoric but all-too-brief rise to stardom. He’d interview most of her immediate family members and loved ones, attempting to complete the tapestry of Zelu’s inner workings and why she did what she did. And, eventually, when Zelu was gone, he’d claim to be the one who saw it coming first.

Readers still on the scent of the plot, will focus on that frustratingly vague referent “it.” What, exactly, did this Seth Daniels see coming? And when are we going to be let in on the secret? But readers coming back to this passage on a second reading of the novel (which this book amply rewards) might wonder something else: Does this passage help us understand the dazzling twist at the end of the novel?

In the last chapter in Zelu’s point of view, we are with her as she blasts into space. We watch her feel a “sweet and sharp pain” and see a jagged white line open in front of her. We wonder, Is this finally it? Is this the ‘death’ of the title? But in the next scene, Zelu opens her eyes and reveals the bright line was metaphorical, a “crack in reality.” She finally gets the inspiration for her next novel, “But she wouldn’t give them this one. She would keep it to herself.” Our interpretive compass for the title swings decisively toward the metaphorical. Zelu will be a writer, perhaps, but no longer an author because to be an author one must have readers.

But the chapter heading on the very next page—“Death of the Author by Ankara”—sends our interpretive needle spinning wildly. In the previous chapter from Ankara’s point of view, we learned that she ultimately thwarted the threat coming to the planet by writing a story, and now we learn that story was Zelu’s. Ankara pushes past the boundary that she and all other AIs had always assumed was there—that only humans could create stories. She tells us, “I crafted her story based on the tales Ngozi had told me of her own life and family history, but I was the one who truly brought Zelu to life, who made her feel real. A Hume. Me.”

My initial shocked disappointment at this twist showed me just how well Okorafor had maintained the “fictive dream” that Zelu was real. The interview chapters added to that illusion. But they also suggest another possibility: That these interviews, in addition to Ngozi’s stories, might have provided the primary materials Ankara drew on for inspiration. We learn in her last POV chapter that Zelu hopes to name her daughter Ngozi, and we’re told by Ankara that Ngozi’s great-grandmother had been an astronaut.

Like an ouroboros consuming its own tail, Death of the Author presents a perfect creative circle: Ankara creates Zelu, who creates Ankara, and on and on. Ankara, however, leaves us with a different metaphor. After revealing that her novel also healed the tribal rift between Humes and Ghosts, she tells us, “I have come to understand that author, art, and audience all adore one another. They create a tissue, a web, a network. No death is required for this form of life.”

Enjoyed this piece? Make sure you are signed up for the Novel Study newsletter, which goes out whenever I have a new essay ready for you.

Want more craft analysis like this?

Novel Study examines techniques from novelists like Ann Patchett and N.K. Jemisin, translating them into practical tools—complete with full-color charts illustrating how successful stories are built.