In my last scene breakdown, on Nnedi Okorafor’s Death of the Author, I contrasted two kinds of worldbuilding: a top-down, expository approach using telling strategies and a bottom-up, immersive approach using showing strategies. My point in that post was not that one is better than another but that they are different tools, each with their correct use. In this post on chapter four of Charlotte McConaghy’s Wild Dark Shore, I’m going to show you those two tools again, this time used for delivering backstory rather than worldbuilding.

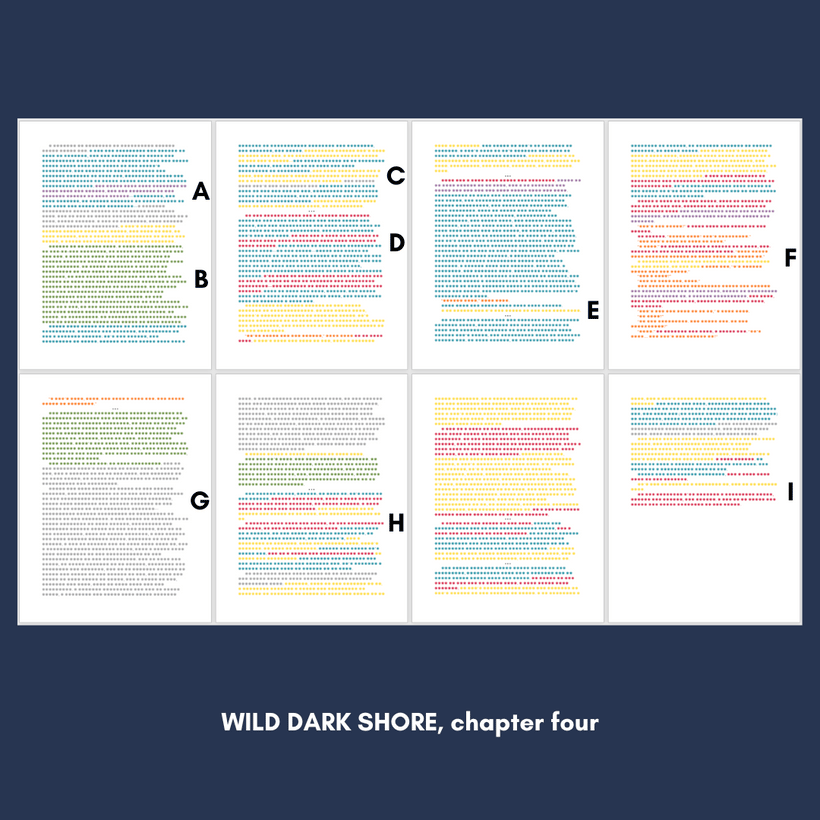

To start, let’s look at the scene component breakdown for the chapter:

Setting 29%

Interiority 22%

Backstory 17%

Action 13%

Summary 12%

Dialogue 4%

Character 3%

In the opening chapters of the novel, Rowan washes ashore on a remote island far off the coast of Australia, near Antarctica. She is rescued and cared for by the family who live in the lighthouse on the island and serve as its caretakers. I analyzed the first chapter, which is in Rowan’s point of view, in my post on the opening. Chapter two is in the POV of the teenager Fen, who finds Rowan, then calls her father and brother to help. Chapter three is in the POV of the father, Dominic, as he and his children tend to this woman, warm her and stitch her wounds, and listen to an especially violent storm rage outside. The first three chapters are all short, a page or two each, and they focus on immediate sensory details and actions.

Chapter four, still in Dominic’s POV, is where McConaghy pauses to fill in some background after this dramatic, high-tension opening. Let’s walk through the first paragraph of the chapter (A in the graphic below), which is a perfect example of expository telling rather than showing:

I brought my children to Shearwater Island eight years ago. I was not expecting the island to feel so haunted, but for hundreds of years the lighthouse we live in was a beacon to men who built their lives upon the blood of the world’s creatures. The refuse of those sealers and whalers remains to this day, discarded along the lonely stretches of black coast and in the silver shimmering hills. The first time Orly admitted he could hear the voices, all the whispers of the animals killed on this ground—including, for good measure, an entire species of seal bashed on the head and wiped out entirely—I thought seriously about taking my children away from here. But it was my ghost who told me they might be a gift, these voices. A way to remember, that surely someone ought to remember. I don’t know if that burden should fall to a child, but here we are, we have stayed, and I think that actually my wife was right, I think the beasts bring my boy comfort.

Notice that we don’t have any kind of setting or action here. The chapter title tells us we are in Dominic’s POV, so we know who the “I” delivering this information is. The matter-of-fact first sentence delivers a crucial piece of backstory that then shades into setting details about the lingering traces of the violent history of Shearwater Island.

But look at what McConaghy does next: Those ghosts in the setting become literal rather than metaphorical. Dominic’s young son Orly can hear them, and Dominic speaks to “my ghost,” who we can infer from the passage is his late wife. More story questions flicker to life for the reader: What happened to Dominic’s wife? Why does Orly need comfort? Is it psychologically healthy for Dominic or Orly to process their grief by way of these ghosts? And how might the new presence of the mysterious woman affect this fraught emotional ecosystem?

Next, McConaghy provides a long paragraph full of summary that encapsulates the family’s day-to-day life on the island (B). It’s more telling, but elevated and enlivened by vivid details delivered with the bell-like rhythm of repeated phrases. Here’s a taste (my ellipses): “A life of simple tasks, of day-to-day routines, of grass and hills and sea and sky. A life of wind and rain and fog… Of hands clasping a hot cup of chocolate… Of the gurgling roar of an elephant seal… Of seeds. Of parenting. Of grappling constantly with what to tell them about the world we left behind.” This technique is called “anaphora”—the use of a repeated word or phrase to create a kind of refrain. (Here’s a good explainer with examples from the Poetry Foundation.)

The takeaway here for writers? When you are using exposition, leaning on telling rather than showing, it’s a good idea to activate additional layers just as McConaghy does here. Make sure your details provoke new story questions or that you enhance your prose using figurative language or rhetorical effects.

At the end of this scene (C), we get a mixture of setting details layered with interiority in which Dominic wonders how the woman could have washed ashore in such a remote and hostile place, heightening the interest and tension of one of our original story questions from the first chapter.

It isn’t until the beginning of the second scene that we get some action (D). It is the morning after the storm now, and Dominic and his older son, Raff, go out to survey the damage. Here, McConaghy switches to showing rather than telling. We learn more about their way of life on this island and more about the setting as the two men assess the damage to their power sources. In other words, the setting details arise naturally out of the actions, from the bottom up. We see specific details (the downed gutters, the scratched solar cells, the broken wind turbines) as the characters see them.

McConaghy drops in a few new sources of tension here: Their comms equipment is down, they will need to drastically reduce their energy consumption to make their dwindling diesel supply last, and the now-empty research station has been inundated by the high tide. A single line of interiority following this last detail immediately elevates the tension of the scene: “I am shaken but I’m not about to let him [Raff] know that.” We understand now that the setting—the wild, dark ocean and the storms that sail across it—is also an actor in this novel.

Next comes another brief bit of action and dialogue (F) as Dominic checks in on Orly, who is watching over Rowan, who hasn’t yet woken. It's not yet clear whether she'll survive (more tension for readers). Dominic then sets off on a hike to check the power supply at the seed vault, which triggers a long section of summary and backstory (G) explaining the history and purpose of the seed vault, and the important story fact that the seed vault is now closing. Dominic and his family will leave the island, along with “all the lucky little specks important enough to be chosen for relocation” in less than two months.

McConaghy does two smart things here: She waits to deliver all of this information at exactly the moment when we need to know it, rather than trying to cram it in sooner, and she positions it as Dominic is hiking across the island. When the next scene opens with him at the tunnel to the vault, we can imagine that we’ve been following his thoughts during the hike, giving the impression of movement even during a scene with no action.

Finally, McConaghy delivers two crucial punches of action in these last scenes that send the external tension of the chapter sky high again. First, Dominic discovers that the power is indeed out at the vault and, what’s more, it is beginning to flood (H). There is a real possibility he will be forced to choose between keeping the seeds alive and keeping his family alive. (This novel is full of moments in which a character is forced to choose the best of two bad choices, a classic technique for increasing story tension!)

Second, when Dominic leaves the vault and goes to the empty field huts where he’ll spend the night, we learn that he had another motive in coming to this part of the island (I). There is something in the blue hut that the mysterious woman can’t see, if she ever wakes up. Here are the last three sentences of the chapter:

It’s not as grim as I remember it, but it is pretty grim.

In the backpack I’ve brought a scrubbing brush, cloths and towels, and bleach. I get to my hands and knees and start cleaning up the blood.

By ending the chapter right here, McConaghy gets a cliff-hanger, but also removes readers from the point-of-view character who could give us the answers if he chose. This is a crucial strategy to remember when there is backstory information you don’t yet want to reveal to readers: In places where we’d expect the POV character to be thinking about that backstory, and thus revealing it, you either need to cut away or give them something else in the scene more pressing and immediate to focus on.

If you are struggling with how and when to weave backstory and summary into the opening of a novel, study McConaghy’s toolkit in chapter four of Wild Dark Shore. Try expository telling, layered with enticing story questions or interesting prose techniques. Or choose scene-based showing that emerges from character action. Whichever you choose, balance a scene heavy on backstory with a punch of action or tension, even if it is brief.

Enjoyed this piece? Make sure you are signed up for the Novel Study newsletter, which goes out whenever I have a new essay ready for you.

Want more craft analysis like this?

Novel Study examines techniques from novelists like Ann Patchett and N.K. Jemisin, translating them into practical tools—complete with full-color charts illustrating how successful stories are built.