SPOILER WARNING

I’m going to talk about the whole plot of The God of the Woods, including the ending and multiple plot surprises. The embedded graphic also gives away many plot elements.

As soon as I began reading The God of the Woods, I knew I wanted to track the way Liz Moore controls the tension and pacing of the novel by strategically opening and closing story questions. The book description introduces two of the key story questions: What happened to thirteen-year-old Barbara Van Laar, who disappears from her camp bunk in the summer of 1975? And what happened to her brother, Bear, who vanished from the same area in the summer of 1961?

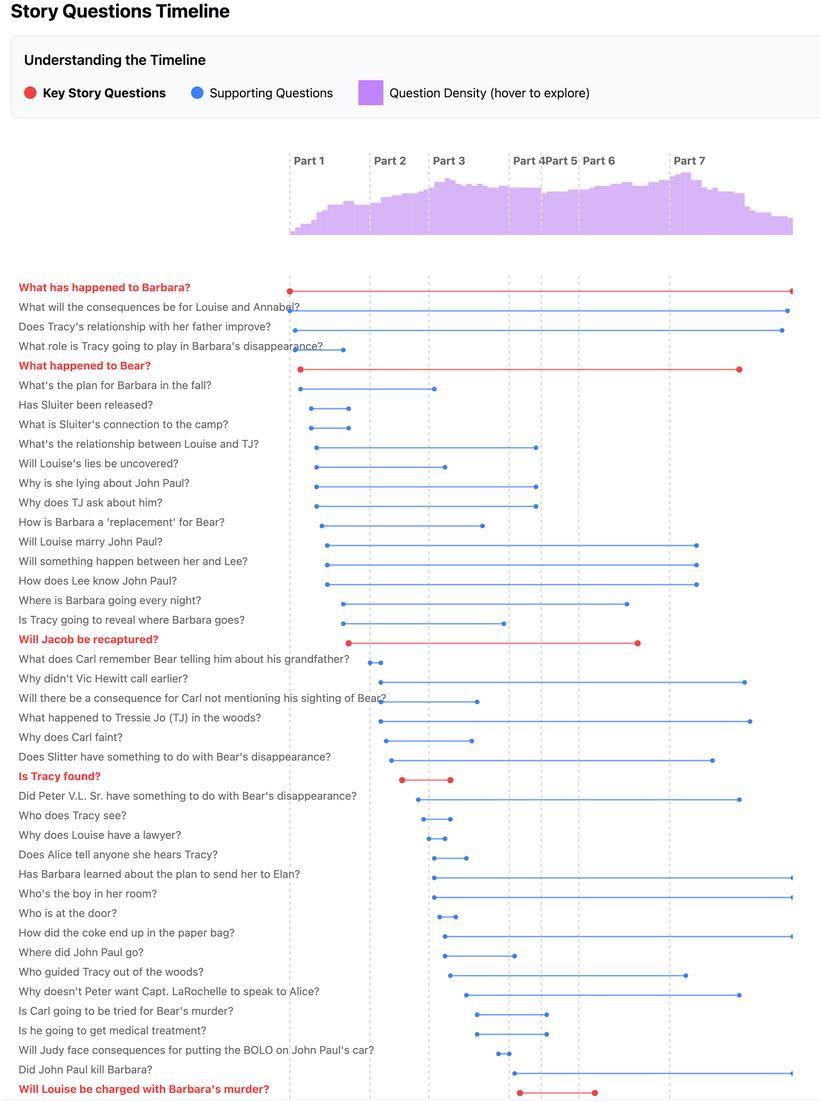

As we’d expect, Moore doesn’t answer those questions until the end of the novel. But to keep readers engaged, she keeps generating new questions. Some of them are answered quickly, after just a chapter or two. Others generate more story questions as soon as they are answered. This data visualization shows the density of open questions as a bar chart along the top, with the 63 questions I identified below and a timeline for each, marking where they are opened and closed in the novel. The highest-stakes questions are in red. (I've included a partial screenshot of the visualization below, but the visualization is interactive and best viewed on a larger screen.)

Looking at the bar chart, you can see that the number of open questions steadily increases through the first third of the novel, dips slowly to hit a low at about the midpoint of the novel, and then ramps up again to hit a peak about three-quarters of the way through the novel. In this final part, Moore answers first the question of what happened to Bear, and then the question of what happened to Barbara, both of which have generated many subplot questions along the way.

An important thing to note about The God of the Woods is that Moore uses a large cast of rotating point-of-view characters to narrate the novel. Readers become particularly attached to the two first narrators we meet: Louise, a twenty-three-year-old counselor at Camp Emerson who is struggling under the burden of poverty, an alcoholic mother, a dependent younger brother, and a wealthy but abusive fiancé; and Tracy, Barbara’s bunkmate and friend, who is struggling with all of the typical teenage angst in addition to her parents’ recent divorce.

Moore builds our sympathy with these two narrators and then promptly increases the tension of the novel by putting them at risk. First, Tracy sets off in search of Barbara herself. In addition to the standard risks of getting lost in a forest that has apparently already swallowed both Van Laar siblings, we know that there is a serial killer with generational ties to this land who is heading her way. Moore increases the tension of this plot further by showing a scene where Alice, the sedative-addled mother of the Van Laar children, hears Tracy yelling but doesn’t immediately report it. Is she going to fail yet another child, we wonder? (We suspect but don’t yet know the extent to which she has failed her own children at this stage in the novel.)

Moore steadily ratchets up the suspense of this subplot until it reaches a climax in chapter 26, which she ends on a cliff-hanger as someone (the serial killer Jacob?) steps out of the woods in front of Tracy. Moore leaves us in suspense for several chapters as she follows other characters and subplots, though we hear Tracy yelling in chapter 28 through Alice’s point of view. Finally, in chapter 31, Moore relieves our suspense. A silent figure with long gray hair guides Tracy back to the road near the camp. Tracy is supposed to be wearing glasses but doesn’t because they make her self-conscious, so she can’t clearly see the figure, and this becomes a new story question: Who did Tracy see? Was it the serial killer, or someone else? Moore finally answers that question much later in the novel, in chapter 75.

As soon as Tracy’s situation is resolved, Moore increases the suspense about Louise’s predicament. Around the midpoint of the novel, we begin to worry that she will be framed for Barbara’s murder. There’s no body, but a bag containing a bloody camp uniform has been found in the trunk of Louise’s fiancé’s car, and he claims Louise gave him the bag. Once again, Moore increases the tension further by having Louise call home from jail and discover that her mother is passed out, her twelve-year-old brother is hungry, and there is no food in the house. She’s bailed out of jail in chapter 58, and the immediate tension eases. Moore doesn’t answer the question of whether Louise will be charged with murder so much as she defuses it, but even the defusing opens a new mystery: Who bailed out Louise? It certainly wasn’t her mother, and we don’t learn the answer until chapter 74.

Cleverly, Moore also livens up the long middle stretch of the novel by revealing that we’ve been given false answers to two important questions involving the Van Laar children. First, we think we know that Barbara is going to meet her boyfriend every night at the observer’s cabin at the top of Hunt Mountain, near camp. This is what she’s told Tracy, and that’s where Tracy is headed when she gets lost. However, later in the novel, in chapter 64, we learn that Barbara has been seen going to the camp director’s tent or cabin every night.

Second, police investigator Judyta learns in chapter 23 when she begins investigating Barbara’s case that Bear’s killer was caught and is now dead, though we don’t get any details and no body has ever been found. At the midpoint of the novel, in part 4, we go back in time to the summer Bear disappeared, and we are introduced to a new point-of-view character, Carl Stoddard, who is employed by the Van Laars as a groundskeeper. We gradually come to understand that Carl is going to be tied to Bear’s disappearance through some circumstantial evidence, but because we are in his point of view, we also believe that he is innocent. Adding this secondary POV character increases the tension around Bear’s disappearance, especially after we meet Carl’s wife and daughter, who later play instrumental roles in solving the mystery of what happened to the boy.

In the last part of the novel, as Moore begins circling the two key questions about the Van Laar children we started with, she relies more heavily on shorter chapters that end with cliff-hangers about smaller questions: What is a potential witness going to reveal? Who is on the other side of a door? Where is one of the key witnesses?

Moore has also structured her ending so she effectively creates not one but two climaxes: All of the remaining questions around what happened to Bear are resolved by chapter 89, and then the plot attention turns to what happened to Barbara, which is finally resolved in chapter 95 when we enter Barbara’s point of view for the first and last time in the novel.

The God of the Woods is a master class in how to manage a complex plot over the course of a long novel. Moore keeps the tension high by continually asking new questions and opening new mysteries, solving just enough of them that we can almost see the resolution hovering over the horizon. We have to keep hiking along the path of pages she lays out before us in order to reach it.

Enjoyed this piece? Make sure you are signed up for the Novel Study newsletter, which goes out whenever I have a new essay ready for you.

Want more craft analysis like this?

Novel Study examines techniques from novelists like Ann Patchett and N.K. Jemisin, translating them into practical tools—complete with full-color charts illustrating how successful stories are built.