SPOILER WARNING

This post discusses the entire plot of Wild Dark Shore, including multiple backstory mysteries.

During our Novel Study Zoom discussion of Wild Dark Shore, one member observed that the novel felt “like a play in a very small black box” and others discussed the “creepy” or “ghostly feeling” that permeates the story. All of a sudden the entire shape of the novel unfolded in front of me and I frantically wrote the words containment and ghosts in my notebook to pin the thought in place

Now I get to walk myself—and you—through what I saw in that moment. Here are my two insights:

First, all novels are, in a sense, containers for ghosts. The ghosts are the backstories that fuel the characters, especially the protagonists and antagonists. These backstories are often the causes in the cause-and-effect engine that moves the plot forward, explaining why characters choose one action or response over another. One of the key questions every novelist has to answer for each new novel is exactly how to weave these backstories into the structure: when and how to reveal the key causes to the reader, and sometimes also to the characters themselves, if self-recognition will lead to transformation (another cause for yet more plot effects).

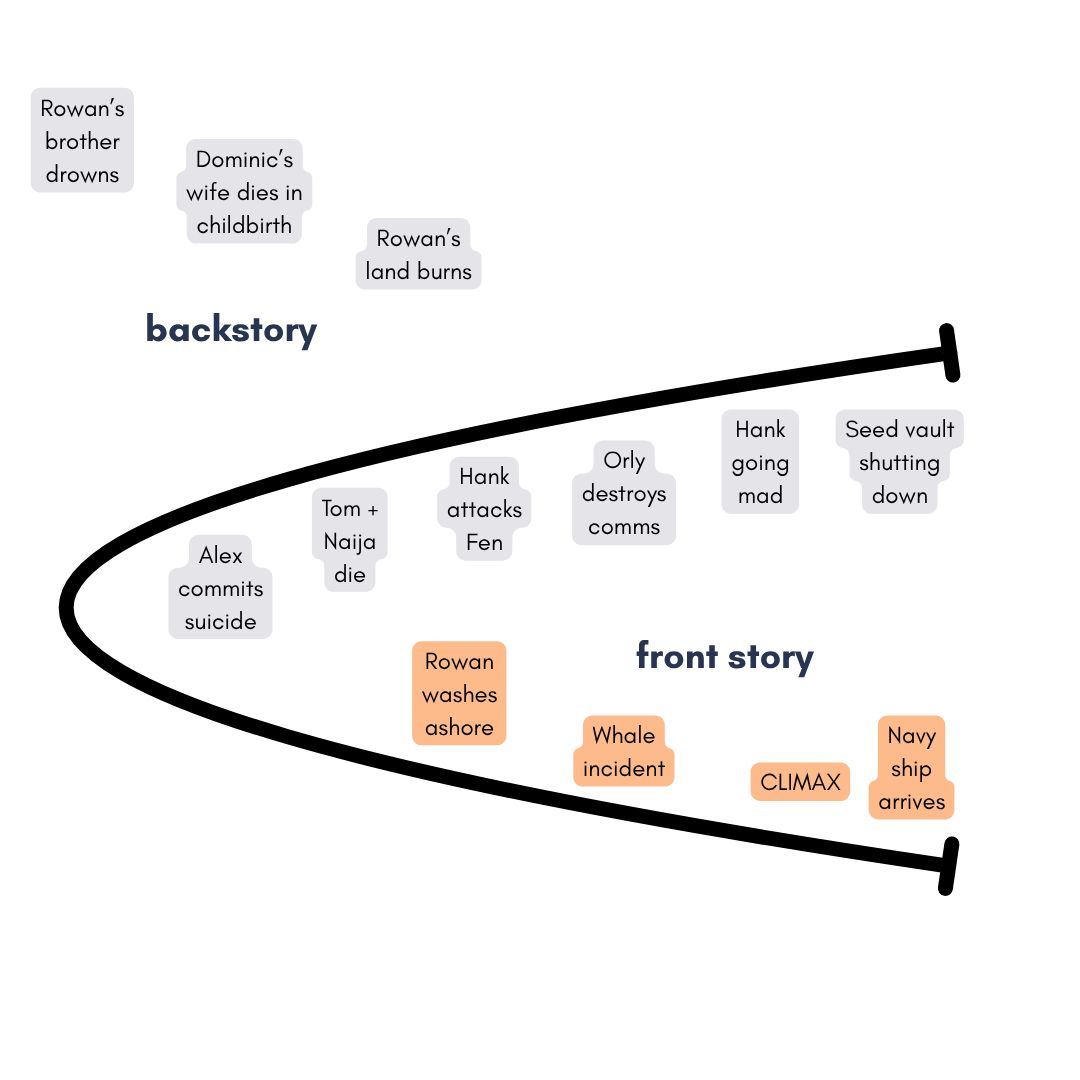

Second, one reason Wild Dark Shore is so effective is that the author has crammed an extra layer of ghosts into the timeline container of her novel, which amplifies the tension and suspense we feel as readers. I’ll walk you through the timeline in detail below but, in essence, the primary characters have old ghosts that haunt them, as is typical for most novels. What’s not as typical is that there are a number of fresh ghosts haunting this novel—events that occurred in the weeks before the novel opens. Another version of this novel might have started two months earlier—and perhaps did in earlier drafts. I’ll walk you through how the structure works and then help you decide whether this is a strategy that could work for your own novel.

Let’s start with the simplest version, which is typical for the way most novels work. The inciting incident is that Rowan washes ashore Shearwater Island, a remote research station near the Antarctic. The only inhabitants are the Salt family, who are in the process of shutting down the seed vault on the island, which is threatened by climate change. The most important of the remaining seeds will be transferred to a new facility on the mainland by a Navy ship scheduled to arrive in about seven weeks’ time.

Rowan, we soon discover, washed ashore after the small boat she was traveling in capsized during a violent storm. The captain of that boat, the only other passenger, dies. Rowan came to Shearwater looking for her husband, Hank, who was in charge of the seed vault and had sent alarming emails about being “in danger.”

As the weeks pass, Rowan falls in love with Dominic Salt, as well as his children, but also comes to realize that there is some mystery about what happened to Hank that they are all keeping from her. At the midpoint of the novel, Dominic’s teenage son, Raff, and Rowan almost drown when a humpback whale leaps out of the water and comes down on top of their small Zodiac boat. The mystery about Hank is finally revealed in the final, high-stakes climax, which occurs during another violent storm that floods the seed vault.

As is also typical, all of our point-of-view characters have various backstory ghosts to contend with: In Rowan’s case, the drowning death of her younger brother when he was in her care and the total destruction of her house and land in a bushfire. In the case of the Salt family, the death of their wife and mother in childbirth.

This array of plot components and backstory ghosts would likely already be enough to fuel a successful novel, but if we pull the timeline of the novel back by just a few weeks, we uncover a sequence of high-tension events that occurred just before Rowan washes ashore. Another version of this novel might have started with the news that the seed vault and research station are shutting down, meaning that the Salt family has to leave the island that has been their refuge for the past eight years.

In the month following that news, Hank begins to go mad under the task of selecting which seeds are preserved and which will be abandoned. Nine-year-old Orly, who has no memory of a life off this island, senses that something is awry with Hank and decides to destroy the island’s comms equipment so Hank will be forced to stay and finish the job—the seeds and animals and ghosts of the island are Orly’s whole world.

In the meantime, Hank has also begun an affair with the seventeen-year-old Fen. When she tells him she is afraid she is pregnant, he tries to drown her. Fen escapes; Dominic almost beats Hank to death, then imprisons him in a storage shaft in the seed vault.

Also in the meantime, Raff falls in love with Alex, who has followed his older brother Tom to the island as a researcher. Raff and Alex spend a night together in one of the research huts. When a violent storm sweeps the hut into the sea, Raff and Alex escape, but Tom and his fiancée Naija drown after alerting them to the danger. Soon after, Alex commits suicide.

In this version of the novel, the Raff–Tom–Alex sequence would likely have been at the midpoint, where we often find an all-is-lost moment, with Rowan’s appearance soon after providing a new twist and additional pressure on the still-unresolved Hank plot.

I think this version of the novel would have also been quite compelling. I could talk about potential weaknesses of this version, but what I’m really interested in showing you is the strength of McConaghy’s final choice for the structure.

Let’s look at that in visual form first before we talk about how it works.

By starting the novel with Rowan’s dramatic arrival on the island, McConaghy effectively traps a whole set of very fresh (and thus very high-energy) backstory ghosts in the now-smaller container of the novel, while the older backstory ghosts are still out in the ether, waiting for their opportunities to haunt the plot. I think it’s this single choice that gives the novel much of its power. Every page is thick with ghosts whose presence we can sense even before we know exactly who is haunting the characters.

Late in the novel, the author actually dramatizes this compression for us. In chapter 57 (page 249), Dominic’s flashback connects all the pieces in a moment that reads like a summary of the structural choices themselves. First, he lays out to Raff, Alex, Tom, and Naija the impossible situation they face with Hank:

We have a man here. He’s had some kind of breakdown. He’s decided he has to drown all the seeds in that bank, and he’s also decided he has to drown my seventeen-year-old daughter. We don’t have any way to contact the police. We’ve got eight weeks until a ship comes for us. So what would you like to do with him?

Then, in the final lines of the chapter, he explicitly connects the cascade of deaths to Rowan’s arrival:

Soon they are dead. Naija and Tom first, and then Alex. And my children and I are digging graves and keeping our prisoner alive, and we are barely holding our heads above water and that’s when a woman washes ashore, seeking to find this man and set him free.

The passage reads almost like a blueprint for the novel’s structure, showing us exactly how McConaghy connects the fresh ghosts to Rowan's arrival and the front story that follows.

From a structural standpoint, this choice also gives Rowan a much bigger presence in the novel. As readers, we begin the novel in her point of view rather than waiting to experience it until after the midpoint. Rowan and Dominic both have twenty-five POV chapters, though Dominic gets much more page time (44 percent to Rowan’s 25 percent).

The strategy also works because both ghosts and containers, those two words that inspired this post, are important thematically and structurally. I discussed ghosts a bit in my last post on the novel, a detailed analysis of how McConaghy deploys backstory in chapter four, but they pop up everywhere. When Rowan almost drowns for a second time, during the whale incident, she has a vivid memory of her younger brother who drowned: “Shearwater is a place of ghosts, after all, and it has found mine and delivered him back to me.” Not long after, Fen decides to free her father from her mother’s ghost by burning her remaining mementos in a bonfire on the beach. That exorcism fails, but in the tense climax of the novel, Dominic’s ghost says to him, “Look at what you have done,” and he is able to recognize the voice not as the ghost of his wife but as the monster of his own grief and guilt and shame.

And the structure, the container, of the novel owes a great deal to the conventions of the locked-room mystery, which intensifies the Hank subplot. If something has happened to him, then there are only a limited number of people on the island who could have been responsible. The island is one container, but it is full of others: the lighthouse, the seed vault, the storage shaft where Hank is trapped and where the climax of the novel occurs.

The seeds in the vault are at once containers and ghosts—harboring the potential for a future plant or tree while also hosting the ghosts of all of the evolutionary ancestors that produced them. Embedding the theme in the structure of your novel and vice versa creates a work that feels magical for the reader, like a seamless, organic whole that is more than the sum of its parts.

Would this compression technique work for your own novel? It could if you are struggling with a story that has too much plot for the length you are aiming for, or if you want to intensify the reader’s experience of the plot. Create a story spreadsheet or rough outline of your plot, then move forward in the timeline, asking yourself, What if the novel started here… or here… or here? If you move a big chunk of your plot to backstory, do you still have enough plot to fuel your ‘front’ story?

The next question to answer is whether and/or how you can effectively inject those backstory ghosts back into the novel. Your two basic techniques are to use embedded memories that are woven into the story in short bits via the POV character’s interiority, or to embed flashback scenes or chapters. (See my Novel Study book or posts for more discussion of these options, especially the chapters on The Last Thing He Told Me and Dial A for Auntie).

McConaghy uses both techniques. One interesting feature of the book is that the flashback scenes are in present tense, just like the rest of the narrative. In our Patreon chat, many of us agreed that this choice was disorienting—there were a couple spots, notably for me on page 183 when Rowan flashes back to the aftermath of the fire that destroyed her house, where I was momentarily unsure where we were in time. But the technique works overall because it makes the backstory feel immediate and urgent, which is exactly what McConaghy is going for.

Enjoyed this piece? Make sure you are signed up for the Novel Study newsletter, which goes out whenever I have a new essay ready for you.

Want more craft analysis like this?

Novel Study examines techniques from novelists like Ann Patchett and N.K. Jemisin, translating them into practical tools—complete with full-color charts illustrating how successful stories are built.